RHEL OSTree images - Intro

A RHEL for Edge image is an rpm-ostree image that includes system packages to remotely install RHEL on Edge servers.

The system packages include:

-

Base OS package

-

Podman as the container engine

-

Additional RPM content

You can customize the image to configure the OS content as per your requirements by using either Image Builder installed on an RHEL system or using Red Hat Hybrid Console.

OSTree RHEL benefits for edge computing

Working with an OSTree based Operating System has multiple benefits when they are applied to edge computing use cases:

-

Simplified management: Secure and scale with the benefits of zero-touch provisioning, fleet health visibility, and quick security remediations throughout the whole lifecycle

-

Platform consistency: Easily create purpose-built OS images optimized for the architectural challenges inherent at edge. It makes the system more reliable and predictable.

-

Efficient over-the-air updates: Updates transfer significantly fewer data and are ideal for remote sites with limited or intermittent connectivity

-

Unattended resilience: Application specific health checks detect conflicts and automatically rollback an OS update, preventing downtime

If you want to know more about OSTree RHEL you can read the article attached below originally published in Medium, otherwise jump directly into the RHEL OSTree images Lab.

A “Git-like” Linux Operating System

Probably you are getting their benefits but you don’t even know that you were using them, I’m talking about libostree Operating Systems.

A “Git-like” Linux Operating System

Probably you are getting their benefits but you don’t even know that you were using them*, I’m talking about libostree Operating Systems.

This is the history of how the needs of a group of developers made it possible, using standard Linux features and concepts borrowed from technologies such as Git, to manage a Linux OS lifecycle as if it were a source code repository.

*If you are using OpenShift, Fedora IoT or RHEL for Edge, you are using a libostree Linux Operating System, just as an example.

![Image from https://unsplash.com/@eprouzet[Eric Prouzet] (unsplash.com)](https://cdn-images-1.medium.com/max/800/0*1rmEc4TRAcHFe_gQ)

Linux is great.

Linux is great…but let’s be clear, sometimes its flexibility gives more than one headache when it comes to Operating System lifecycle management.

We tried to overcome the challenges that we find while deploying, patching, upgrading, onboarding, decomissing, observing, recovering, and debugging Linux Operating Systems by using a specific set of tools that get the most from the OS features at the same time that simplifies and amplifies the management operations for our preferred Linux distribution.

We have tools that standardize the version of the binaries and software installed across multiple systems, tools that patch the OS if a new vulnerability is found, and tools that recover a previous state if something really wrong happens with your Linux, … but what if I tell you that there is an approach to solve these and other lifecycle management challenges? What if I just could manage the different OS lifecycle updates as if they were rooms in your own hotel, where I could sleep in a new one with a different view, bed, or decoration, but where if it does not convince me I could always go back to my preferred one where I feel comfortable and safe?

Note: This is a long article, so I will be nice and I will tell you a secret, at the end of it I’ve included a summary that tries to cover the topic at high-level and outline the benefits of this kind of systems.

Why do we need “something” different?

When it comes to technology, sometimes “less is more”. If your smartphone provides a GPS map APP you probably won’t buy a physical GPS navigator. If your Linux can provide effective and easy-to-use out-of-box features, why would you need to configure and maintain any additional tools?

Think about the complexity (and cost) of the solutions out there that are promising Operating System rollbacks, incremental updates, OS consistency, or binary change history tracking. Wouldn’t be nice if I could accomplish that with just OS features? Of course, this statement can only be true if the out-of-the-box feature is, at least, as good as the ones provided by additional tooling, but we will see in this article how this new lifecycle management approach can provide these features and more.

You will also see how this “something” different, let’s call it libostree (name OSTree is also used), that started to provide a way to perform a more effective development, brings benefits that are the perfect match to cover the gaps that we find in many other fields, from Edge Computing to Hybrid-cloud use cases.

After that, we will see how common problems of several solution use cases will greatly benefit from the usage of libostree Linux.

Being in “Jail” is not always a bad thing

Some years ago, some people were struggling with the complexity of developing using core aspects of the OS without “breaking things”, or at least having a safe way to “break things”. They ended up writing down a set of capabilities that they would like to have implemented to simplify the development (of GNOME) by being able to quickly create a new “instance” of the OS in the same system where they will perform some changes that could be easily reverted… but that will also cover several additional needs, such as sharing data between these multiple “versions” of the OS, using the system installed apps, specific hardware usage, etc…

Getting a new “OS instance” could be accomplished using technologies such as virtualization, containers, etc… but the creation process is slow (ie. create a new VM or building a new container takes some time) and access to the same system data, applications, and hardware is not always easy, along with that the kind of rollback capability that they were looking for was not trivial sometimes. They needed something else.

Based on those core requirements, and after reviewing some alternatives (virtualization, containers, BTRFS,…) they decided that “chroot” could be a good candidate as the foundation of something new that could help with the gaps they found.

“Chroot” is an operation that was introduced in the early days of Unix that changes the apparent directory used as “root directory” by the system, making it possible to create a “jail” environment for the applications running on it. It is used to create sandboxes for processes, so they cannot maliciously change data outside the chrooted directory, or as a lightweight substitute for VMs (remember they needed to “quickly create a new OS instance”, so it seems to be a good choice).

It could also sound familiar to “containers”, isn’t it? While the concept is similar, with the container “namespaces” you get additional isolation, which will prevent you to access certain OS resources that you would like to keep sharing… something that you can get when using “chroot jailed environments”.

Their idea was to make it possible to boot from different chroot directories, so they could potentially develop new features on one jail environment, being able to access some shared data along with other applications and, if they break something, just go back to the “original” chroot jail that wouldn’t be affected by their changes.

But just using chroot was not enough because in order to provide these capabilities you need to make it work with other different bootloader components like GRUB, kernel init files, FS mount, etc… and not just only that, you need to take into account how to perform certain operations such as platform updates… and that’s what libostree is all about.

A “Git-like versioning model” for bootable filesystem

If you want to read a formal description of what libostree is you can check how it is described in its own source code repository:

https://ostreedev.github.io/ostree/[libostree

__This project is now known as “libostree”, though it is still appropriate to use the previous name: “OSTree”.

Libostree is both a shared library and suite of command line tools that combines a “git-like” model for committing and downloading bootable filesystem trees, along with a layer for deploying them and managing the bootloader configuration.

In other words, libostree is the missing piece that you need to have and maintain the lifecycle of a complete bootable Operating System based in multiple chroot jail environments… but wait, probably something got your attention, it says that libostree follows a “git-like model”. Why is there that reference?

Let’s step a little bit back. We have been talking about using chroot to create different “versions” of the root filesystem that could be booted. Those versions will probably have a lot of files that are identical to each other. Coping the same files into each “chroot jail” would consume a lot of space, then there must be another way to have the same files in different root folders but with neither replicating nor sharing them at the same time that you keep track of the version changes.

You might not be an expert in Git, but you probably know a little bit about storage technologies such as Object-based storage concepts and how unstructured data that is stored in a flat data environment can be described by using hash strings, like a key-value data store that binds the hash with the file metadata and finally with the actual data bits. Git works in a similar way.

Git is a database of objects identified by hash that are stored using a key-value data store concept. It has 4 different types of objects which identify the content of a file (blob), the directory structure (tree), the “versioning” info (commit), and annotations (tag).

While “blobs” and “trees” are enough to represent a complete file system, the “commits” contain the reference to the “tree” object describing the root directory of the repository, which provides a full versioning system. Two different versions could point to the same “blob” if the bits between versions didn’t change, which results in not having to replicate the bits between them.

Git seems the perfect match for what we are looking for, why not use it instead of creating a new git-like “thing” (libostree)?

Note: If you want to check out the libostree objects you can find them here: https://ostreedev.github.io/ostree/repo/

I’ve already shared one reason, we need additional specific features to make the versioned filesystem become an actual versioned Linux bootable system (GRUB, init files, etc), but there is something more. Git was designed as a source code repository versioning system, which means that its features are focused on “text files”, in contrast, what we will need is mostly versioning of a mix of “text files” and “binary files” so the features must be optimized for both, not just text. For that reason, libostree is not just Git, it uses Git concepts and applies them in a very similar way, but the implementation is not exactly the same one.

File “replicas” without multiplying the space needs

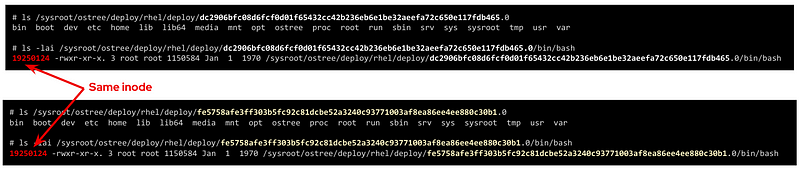

Now that we understood that chroot is the right technology to create the “jailed” root filesystem environments and that we would like to have a versioning system similar to what we get with Git, we need the Linux functionality that glues them together, and that is the file “hard linking”.

In Linux, we have two kinds of file links: soft and hard links. While soft links (symbolic links) are a special kind of file that points to another regular file (which points to the data), hard links are different filenames pointing directly to the same data and attributes (inode).

The two different types of links exist because they offer different capabilities. There is a key difference between them that makes hard links better suited for our git-like versioning use case. With hard links, if you delete the “target” file you can still have access to the data, while with soft links if you delete the target file the symbolic link will stop working and become useless. We need to have multiple “file replicas” on the same disk partition, and those replicas must be independent, so when you delete one file you wouldn’t like to “auto-delete” the rest of the “replicas”…

So it’s clear that soft-links are not an option and hard links are the way to go… but there is something else to bear in mind when using hard links…

You won’t break it if you cannot touch it

We have seen how Hard links provide the benefits that we saw, but its usage also has a big implication that we need to address: if you change the content in one hard-link file and so all the remaining file hard links pointing to the same inode will be changed too.

Why is that an issue? Imagine that you have two OS “snapshots” (let’s start calling them “deployments”) in your system: deployment A, and deployment B which are identical. While running on version B you change a binary version, but after that change, you realize that something is going wrong and you revert to version A…. the problem is that the same change that you did in deployment B, and which broke the system, is applied to your deployment A too so you won’t get rid of the issue that you created.

What’s the best solution to solve this problem? Well, actually it’s pretty simple: by default, do not allow to change anything.

Instead of allowing file changes like in a regular Operating System, making it necessary to build a complex change tracking system to be sure that any operation that changes a file is recorded to be processed afterward so you can revert it, you could just prevent changes by default and build a way to perform changes only under the control of your versioning system… and libostree was designed around this concept.

In order to prevent the changes, the Operating System is built on top of a read-only filesystem, so it works like an “image snapshot” of the root filesystem of the operating system, but of course, libostree need also to provide a method to perform effective changes to those images.

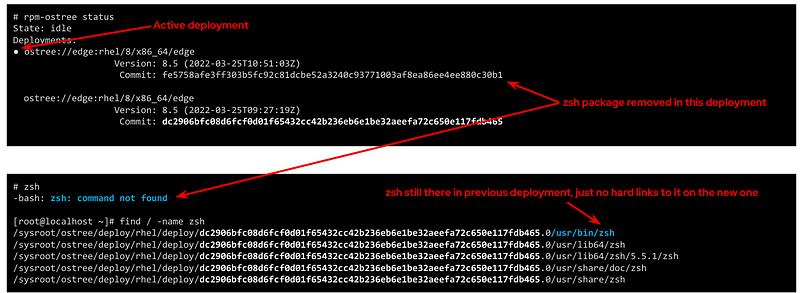

When you need to perform one (or a set of) changes, a new replica of the whole root filesystem is created (remember that that does not mean to double disk space needed and that creating that replica is quite fast) and the changes will take place on it. The files that you didn’t touch will remain as hard links, while the modified versions will become a new “regular” file or be deleted as in the example below.

Note: deployments can also be deleted to save some disk space, for example in this case if you won’t need zsh anymore you could remove the deployment that contains the binary (but remember that it will only free the size of that binary if that was the only change between deployments, the rest are just hard links)

Read-only does not mean do-not-update at all

Let’s say that you have several application binaries that you would like to update, as we have seen, you need to create a new replica of your chroot filesystem with the new versions of the binaries but, how do I use that new replica?

When you are running in a deployment (remember deployment=filesystem version/revision) and create a new chroot directory with the changes, you are still running on the source version, you don’t instantaneity move to the new deployment… you just made a bunch of new hard links…. How do you make effective these changes to the “running OS”?

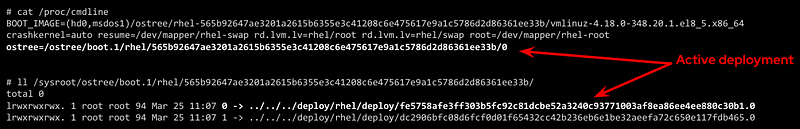

With libostree, at system boot time, one of the available OS root “snapshots/images/deployments” will be selected by following a symbolic link located in a specific place on the filesystem, so if you want to use any alternative root filesystem image (for example, the one with our new binaries) we just need to change the default (0) symbolic link and start pointing to this new filesystem “release”.

How is that included during the boot process? There is a new kernel argument in the initramfs file specifying the soft-link (which points to the deployment chroot filesystem).

We are talking about performing that change “manually” or as a part of the upgrade process, but there are even implementations that automate the deployment rollback in case of errors such as Greenboot (available in RHEL for Edge and Fedora libostree variants), which permits to include scripts that check whatever thing that you find important, from any specifics from the system to the service provided by the application running on it and, if those tests fail as part of a system update, Greenboot will change back again the deployment and reboot to go back to safely automatically, with no external intervention.

One thing important to mention is that the decision about what filesystem snapshot (deployment) is used, as mentioned before, is done at boot time, so if you want to change to a new deployment you will need to reboot your system to make the changes effective.

This is different from the “regular” package-based Linux distributions where (sometimes) you can update your binaries without the need to restart your system, but this change-at-boot also assures consistency across all binaries and running processes, which is a great benefit of image-based systems. And remember, thanks to this consistency we get one of the coolest features of the libostree Operating Systems: system rollbacks

Think about that, we selected a “new filesystem version” to be booted on the next restart… but nothing prevents you to select a previous version instead since we are using consistent filesystem images/snapshots, it’s just a matter of where to target our symbolic link to.

All this means that you can track root filesystem versioning following the same methodology that you use with Git source repositories, make changes without affecting previous deployments, and switch between versions as easily as changing a simple symbolic link…This is a huge benefit!

But there is more. We talked about generating new “images” of the OS that will update the system. We could be thinking about generating the images on the same system that will be updated… but better think about centralizing this operation in an external place, which gives you several benefits.

Probably you don’t have just a single system that you will be maintained, you might have tens or even thousands of them (ie. Edge Computing use cases). In that case, you could generate the updates on a central site, publish them on an HTTP server (or send them over physical in a USB) and then make the systems either update automatically or just download the new deployment (OS “image”) and wait until the right moment to apply it.

This approach simplifies a lot the management at scale but also permits to have the change tracking in a central place (when, what, who). And additionally, another benefit: when you install Software packages, you will be only calculating the dependencies, executing the %post scripts, performing the SELinux labeling and downloading the repositories the dependencies once in the central location, instead of having to waste the compete and network power one time per system, since you will be installing the packages at the image that you are creating in that centralized place and that will be shared with all the rest of systems.

And talking about Software packages, probably when I create a new OS image revision I will need to add or remove Software Packages, but I’m generating the new deployment with libostree now….

Does it mean that I don’t need any Package System?

You might be thinking…if libostree is the one who manages the updates of the system… I don’t need any package manager (APT, DNF, etc)…well, no, libostree is not a package manager and you probably want to install one in your system.

A package manager is a tool that simplifies the management of Software packages (install, remove, update or configure), which are archive files containing the pre-compiled binaries and configuration files that shape an actual Software application. These packages were created to remove the need of compiling Sofware from source code in order to install something in your system.

Libostree only manages complete bootable file system trees, not individual files, actually, it has no knowledge of individual files at all (how they were generated, their origin, …) so it needs a separate mechanism to install additional packaged applications. You still need a package manager if you want to keep the simplicity of packaged Software instead of coming back to compile from source code on your own like in the not-that-good-old-days.

But you cannot use package managers as they are, since they probably don’t expect to have your OS in a read-only filesystem. You need a “hybrid” package manager that knows how to deal with libostree.

In RHEL for Edge and Fedora systems, for example, you have the rpm-ostree hybrid package manager which combines the libostree updates with RPMs packages, using the same /etc/yum.repos sources but including the RPMs as a layer on top of the libostree system.

How is that “combination” between libostree and rpm done? DNF installs the packages in the filesystem created by libostree (copied from the original deployment), and then a new image is created from that modified copy of the original filesystem containing the required rpm packages which will be the actual “new version of the libostree deployment” (in contrast with the intermediate image that was created at the beginning by libostree). It probably will be better understood by reviewing the steps of an update performed with rpm-ostree:

1. libostree checks out a copy of the filesystem as we saw previously

2. DNF installs packages into that new filesystem copy

3. libostree checks in the copy as a new object

4. libostree checks out the copy to become the new file system

5. Reboot to pick up the new system files

What about the configs and user data?

We have been talking about the need of mounting the root OS filesystem as read-only to prevent changes on the file hard-links out of the libostree control, but any OS will need write access to configuration files, or user data, so you cannot make all the OS directories read-only.

Actually, by default, libostree mount just /usr as read-only and include all the directory trees that should be not modified there (ie. libs, bins, etc) but to be honest, there is way more, as an example, I can tell you that in /usr/etc you can find all the /etc files that were changed giving you the chance to include cool features such as “return system to factory configuration”.

Regarding those directories that must have read/write permissions, there is something else to be considered. There is one differentiator between “writable” OS files that creates two sub-groups here. There are files that are attached/bound to a specific OS deployment while others will need to be “independent”.

For example, let’s suppose that in deployment “A” I have an application in version “1” which needs a configuration file that would need to be writable (so you can tune the config without having to create a new image). Now you update the application to version “2” so you create a new deployment “B”, but in the application release transition, developers changed the configuration file options (maybe including or removing parameters, or even changing the configuration file format), so the configuration files must be “dedicated” to their respective deployment in order to make possible that the application can find the expected configuration file for each release. In contrast, my applications won’t be affected by what kind of cat pictures I downloaded from Internet between the different OS deployments.

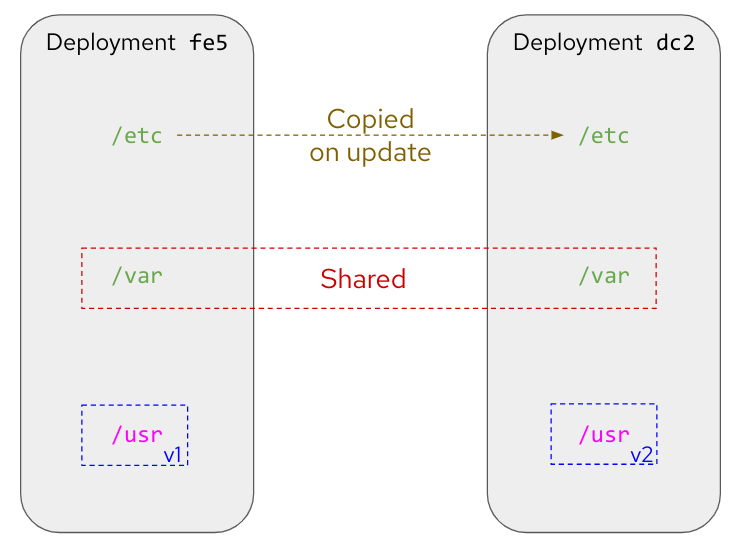

So in summary, there are cases where the writable files must be replicated along with the read-only file systems when a new deployment is created, and others that just are shared between them (they are not “copied / replicated / versioned” when new deployments are created). For writable files that need to be bound to specific deployments, by default, libostree uses /etc while for files that are independent and that will be shared it uses /var.

There is a special case that I didn’t touch on so far: User and Group management. Users and Groups are usually configured in /etc/passwd and /etc/groups files, so they would be part of the “writable files associated with a specific deployment” which could make sense for “system users” that execute OS processes, but the problem is that admins could also potentially create additional “regular” (dynamic) users. Why is that a problem? For example, when you deploy for the first time a libostree OS you will have a /etc/passwd (“v1”) file. Imagine that an admin using that first deployment creates a new user “luis”, which will imply to write in /etc/passwd`so it will become “v2". Now imagine that at the same time, I want to include a new system user as part of the libostree update. The conflict arises because the libostree update process (I’m not talking about modifications made by RPMs) does not write over the `/etc/passwd v2 including the new system user, it would do it in the /etc/passwd file “v1” because that’s the one that it finds in the chroot OS snapshot. What it will do in fact is to check the status of the /etc files, and then it will find that /etc/passwd has been modified from the “template” version (v1), so it will maintain that version (v2), making it impossible to include additional system users if someone modifies the /etc/passwd file (same for groups in /etc/groups). what could be done here?, libostree does not impose a solution for this corner case, but in Fedora/RHEL distros you find a possible solution: nss-altfiles . This piece of Software permits to include of additional files describing users and groups besides /etc/passwd and /etc/groups, so the solution is to create a file that will be bound to the system users in the chroot read-only filesystem (/usr/lib/passwd and /usr/lib/groups ) and use nss-altfiles to add that information to the ones described in /etc/passwd and /etc/groups which will hold the dynamic users created by admins.

Let’s forget about corner cases and go back to the simplicity of writable directories “bound” or “not bound” to a deployment.

Now that we know that /etc is used to host files that are bound to specific deployments, and in`/var` there are files that are independent, we can easily understand what happens with those directories when a new deployment is created by libostree: the /etc location is copied, so when it performs a dnf install (if you are using rpm-ostree), which could potentially change the config file format, it will modify the new copy associated with the new deployment, and let the old one untouched. At the same time, /var is just shared between them so the same files are accessible in both deployments.

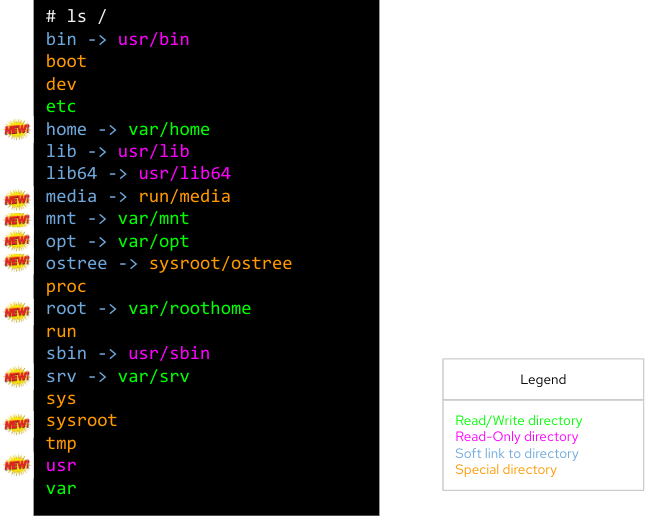

Each libostree Operating System can decide what to put on /var, but it’s a good idea to include there the users' home directory (traditionally /home) so they can write and keep their cat pictures downloaded from Internet. We can take a look at the directory distribution in RHEL for Edge as an example, and compare it with the non-libostree (“regular”) RHEL directory tree (check out the “new” tag for changes):

We can see here how /usr is mounted as read-only and. In order to maintain the common Linux directory structure, several links were created to the new location (in /usr), I’m talking about directories such as /lib or /sbin. You can also check that /etc and /var have write access and how /home or /root are redirected to /var along with other directories that contain files that are “independent” from the OS deployment.

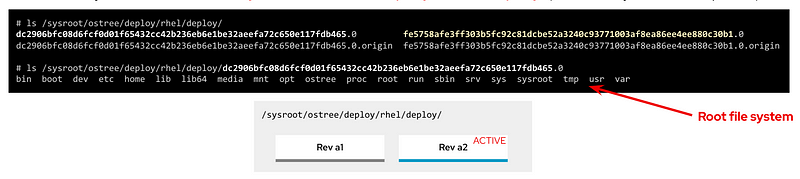

The rest of the directories are “special” locations that you can find in Linux distros, but you can also find a new /sysroot directory along with a new /ostree link. As we saw, our root directory tree is in fact a chroot jail, which means that your / “virtual” directory tree is in fact hosted “physically” somewhere else (along with other / from different deployments). That “real” place where the different chroot directories are holded is /sysroot, in fact, if you check the screen captures that I included above to demonstrate the different OS deployments using chroot, you will see that they are placed in /sysroot/ostree`and that’s also why the `/sysroot directory on each deployment chroot directory is empty (because it must “really exist” on the system, outside the chroot jail).

I should have included a TL/DR in this article…

…although if you have read all this “stuff” until this point, you probably don’t mind if I add a quick summary here.

We have seen how there was a need for a quick way to “fork” the Operating System (including data and Hardware device access), where you could rollback to the original version easily. They need that in order to develop and test Software that could break the system in a safe manner. After exploring multiple alternatives (virtualization, containers, etc) it was clear that a new way of managing the OS lifecycle needed to be created because the alternatives didn’t cover all the gaps.

One idea started taking form: What if we manage the Operating System following the same Git concept as if it were a source code repository where you can fork, roll back, track changes, etc… ?

Once the idea was clear it was only needed to choose the right Linux main technologies and features that would permit to implement the Git concept for the OS lifecycle management, and the answer was: chroot and file hard-links:

-

chroot to isolate the different OS root filesystems (forks)

-

File hard-links to avoid file duplicates between the different OS root filesystems (limiting the impact of cross-changes due to linking with read-only filesystems)

With those components as the foundation, a new approach to the OS update lifecycle was created, and the new technology was called libostree, also known as OSTree.

Libostree is a new system for versioning updates of Linux-based Operating Systems which brings several benefits:

-

You can perform transactional upgrades (which can be done incrementally over HTTP)

-

You can perform rollback for the Operating System (including auto-rollback if something is not working after the update)

-

You can centralize the image generation, which provides OS consistency across multiple systems and also reduces the amount of computing power and network bandwidth needed to install Software packages (with rpm-ostree)

-

You can have prepared multiple OS deployments (parallel installs) where you can boot at anytime

-

You have a track of changes thanks to a versioning system inspired by Git source-code repositories

But why a libostree OS could be interesting to me?

I know that you like to learn new things to expand your mind and wisdom, but let’s focus just for a moment on the practical side of the libostree / OSTree concept. We have seen the benefits but, how is it relevant for any business/technical use case?

The benefits that you get out of a libostree OS could be applied to multiple use cases, but let’s focus on two of them.

Container-focused Operating System

Maybe you have realized that the way that we perform updates and rollbacks in a libostree-based OS is similar to what you do with containers, where you can use different container images versions from the container image registry, selected based on labels, and that you update by performing “a restart”. But there is more, the architecture is also similar since both boots from read-only disk and keep user data on different volumes.

The lifecycle of both have similarities and the good side is that with libostree-based systems that are running “only” containers you could completely split the lifecycle of the applications (containers) from the lifecycle of the OS, but at the same time you can follow the same practices for both.

Note: As you can imagine, eventhough both tradicional and containerized workloads can be executed, containers are preferred since they have an independent life-cycle from the current Operating System image deployed.

For those reasons, you find libostree Operating Systems such as Fedora/https://docs.openshift.com/container-platform/4.11/architecture/architecture-rhcos.html[RHEL CoreOS], which is used as the Operating System that hosts the OpenShift Container Platform.

Edge computing

This is another interesting use case. In a previous article relative to FIDO device onboarding (FDO) feature (link below), which is quite interesting for Edge Computing use cases and which is available on RHEL, I introduced some common aspects that you find in an Edge computing solution architecture.

https://luis-javier-arizmendi-alonso.medium.com/edge-computing-device-onboarding-part-i-introducing-the-challenge-59add9a86200[Edge Computing device onboarding — Part I— Introducing the challenge

__This article outlines the challenges that you will face while performing a secure device onboarding at the scale…

I will copy-paste that list here:

-

It will be capable of working in small HW footprint environments

-

It will work at big scale

-

It will tolerate network disruption (or being disconnected)

-

It will be fully automated with a central point of management and observability

-

I will secure data at rest and in transit (even against physical threats)

-

I will be able to be integrated with external IT and OT systems and protocols

If you paid attention to the benefits stated about libostree, you probably can see how some of its features are the perfect match to cover the needs of Edge Computing architectures. Just as a quick example:

-

Updates are atomic and are done incrementally, only downloading the differences, so it provides better usage of the computing power and network bandwidth that are essential to reduce resource consumption at edge locations (not-good-enough networks, small HW footprint environments, …)

-

You also get less resource consumption (compute and network) while installing or updating Software packages, since as we saw, all the dependency calculations, %post scripts executing, SELabeling, and repository downloading are done once at the central site, opposite to having to perform the same task one time per system (which could be huge in Edge Computing environments) in locations where network and compute power capabilities are not the someones that you could find in a Data Center.

-

When you work at scale you would like to have a consistent platform where you don’t have different Software versions in different locations on systems that should perform the same task. You get this out-of-the-box thanks to the usage of OS images (libostree commits) that can be distributed both online or offline to the edge locations. And it is not just consistency, the usage of images also gives you better reproducibility.

-

Probably in the Edge Computing remote locations, there are no specialized people that could install or perform troubleshooting of the devices (more about this in the FDO article above), so having a system that you can update and, if something starts failing, you could rollback either manually or automatically is a great advantage

-

Although it is not something exclusively of Edge Computing environments, when you work at that scale is quite beneficial to get the change tracking capabilities that a Git-like system provides

These are some of the points why the usage of libostree Operating Systems as the base systems on Edge Computing devices is a good idea, and for example, it is why some embedded systems manufacturers are moving away from old “dual-bank” architectures and providing libostree devices.

I’m convinced, how can I play with a libostree OS?

Good!, I will give you two options here.

Note: If you have OpenShift probably it is not a good idea to start playing with CoreOS since the whole management of the Operating System is performed by OpenShift

The first one is going to https://getfedora.org/ and choosing any of the editions that I marked with a red square below.

For example, in my case, I’m running Fedora Silverblue on my laptop, and to be honest, the rollback functionality was super-useful. I will share a personal experience. One time I updated my laptop during the afternoon while the next morning (9 am) I had an important meeting…. Imagine what, my NVIDIA drivers decided to prevent the OS start. I couldn’t imagine that because it was the first time that something was not working after an update in Fedora (I don’t have the same experience with other distros), but what I did then is rollback to my previous deployment (before updating and where my NVIDIA drivers were still working), deliver a successful presentation and after that, when I had time, I fixed the issue to make my system work again with the new update.

I suggest trying Fedora Silverblue as the first step since Fedora IoT is kind of special since you need to perform additional steps to get your image ready to be used.. this can make it your second libostree distro to be tested.

But if you want to go with an option more “Enterprise ready” I would suggest checking RHEL for Edge which actually is similar to Fedora IoT but where you own the Image building process too, so you can also learn about it.

You could start from the official docs but if you want a quick ramp-up you could use the “quick-start” scripts that I created (link below) to simplify the RHEL for Edge image creation.

https://github.com/luisarizmendi/rhel-edge-quickstart[GitHub - luisarizmendi/rhel-edge-quickstart

__These scripts help to quickly create and publish RHEL for Edge images.

That’s all!

I hope that you enjoyed reading this long article and that you cannot wait to start exploring the libostree OS benefits on your own.

Thanks for reading.

Exported from Medium on November 30, 2022.